Act 1: The Color Purple, black women, and art as worship

Act 1: The Color Purple, black women, and art as worship

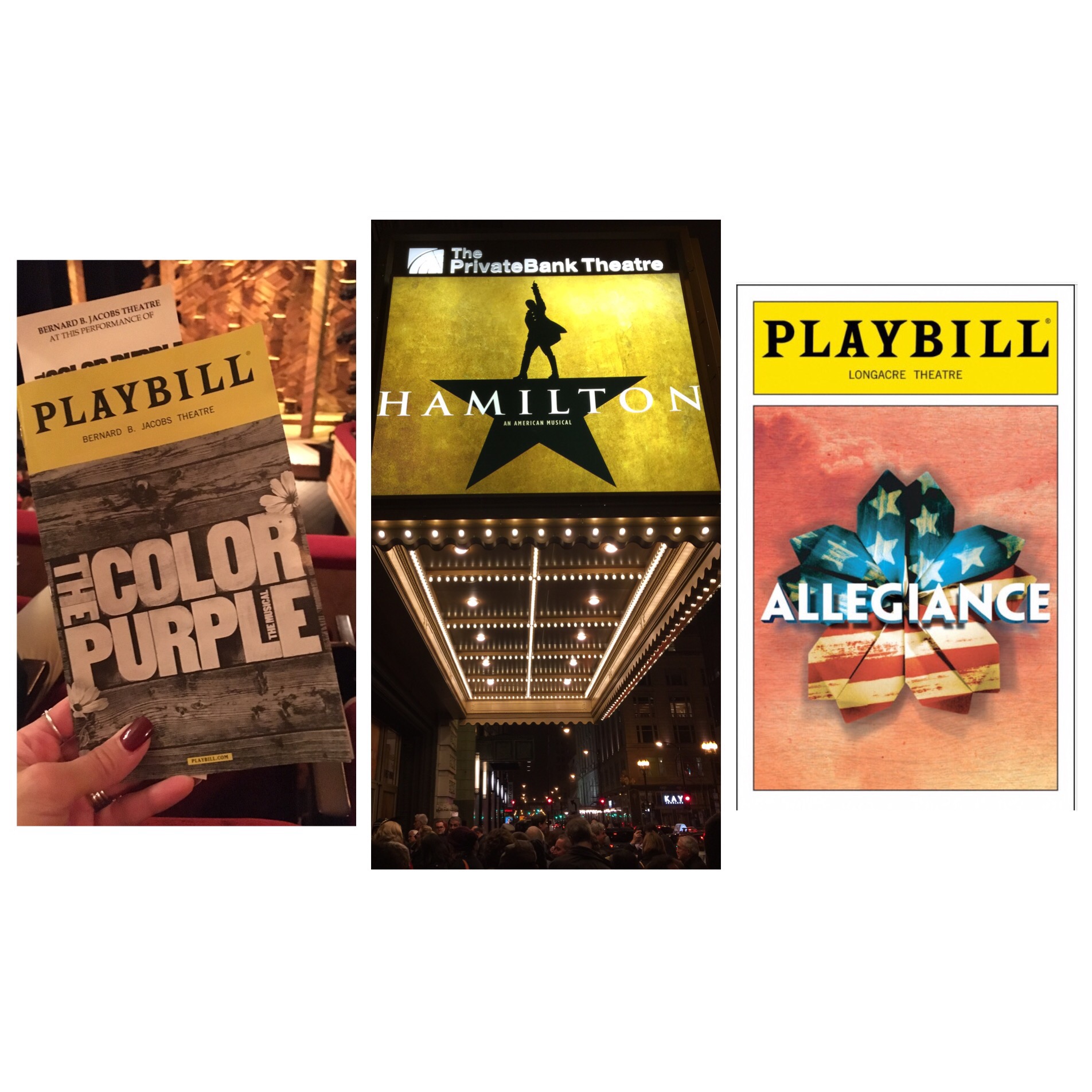

When in NYC I make sure I to make time to see my daughter and to see a show. Bonus points if she and I can go together and this time it was to see and listen to Cynthia Erivo and Jennifer Holliday in “The Color Purple”. The final show is January 8 so if you have the time and $$ to see the show, do it. It’s worth it.

Despite #oscarssowhite, Hollywood and Broadway and creative spaces in between remain predominantly white spaces. Universal stories are portrayed through the acting, voices and creative direction of white people. Yes, it’s changing. Yes, I’ve heard of Lin-Manuel Miranda. Yes, I’ve also heard of Shonda Rhimes. Yes, it’s changing AND there is A LOT of catching up to do.

When I am in new public spaces I tend to look around and observe who is and isn’t in the room where I happen to be. Unlike some people, I am not colorblind so I took note that the audience for the matinee was diverse with as many, if not more, people of color in attendance. Why does that matter? Because it’s easier to stereotype POC as being poorer, less-educated, less likely to attend musical theater, etc. than to ask “Why are not more POC making it a priority to see live theater?” when n reality it’s much more complex.

Back to the musical. I wasn’t sure what to expect in terms of the staging of a story I had first seen on the big screen, but in the end I was left with the experience of having been at church. Some attendees were there for the spectacle of it all (like the white man seated on the main floor, center orchestra, who whipped out his cellphone to take a photo or video of Ms. Erivo singing like no one was going to notice. Ms. Erivo noticed, called him out publicly, and went on without missing a beat. Did the man not read the program or understand the announcement?) while others were there hungry to connect.

If you aren’t familiar with the story, you can read the book or watch the movie. I highly recommend it because as we creep towards inauguration day it’s a good reminder of what history has demanded of black women – their strength, perseverance, bodies and hearts. I sat there thinking of the black women in my life who have graciously shared their lives with me IRL and through social media. The Color Purple isn’t a story about the magical negro who comes to save and touch the life of a white person. It’s the story of black women being themselves – happy, loving, angry, confused, hopeful, faithful, petty, and fully human finding themselves in their own skin and soul.

And it was in the voices of Celie, Nettie, Sofia and Shug Avery I went to church, which was important for me because it has been a long summer/fall without consistently being at church. The irony and subversive nature of non-black audience members giving the all-black cast a standing ovation for singing and dancing about the pain and beauty of post-slavery life in the South weeks before DJT was elected as #PEOTUS (#notmypresident) should not be lost. It’s exactly that tension that has made attending church regularly such a losing struggle as of late, but there I was, on Broadway, in church wrestling with God about injustice, violence against women, love, sisterhood, motherhood and the silencing of women, particularly black women not only in the church but in history.

If musical theater can communicate good news, what is the Church missing in its gospel expressions?

Act 2: Hamilton, white women, and subversive art

At a much higher price point was seeing “Hamilton” in Chicago with the family as part of our Christmas gift. As the children are in their teens and 20s stuff is less prominent on their wish lists. They don’t want toys. They want gas money. They want money for an extra plane ticket. They want a dog. They will never get a dog so we are now in the second year of going to see live theater together as part of Christmas. Lucky for them I sat patiently on two computers, one phone and one iPad to get through the online ticket queue.

The audience was less diverse though I suspect the commercial success of this production lends itself to its broader appeal in terms of ethnic/racial diversity and age. There were many, many more younger audience members who wanted to see U.S. history via rap battles and F-bombs. Other than pure commercial success drawing a whiter and younger crowd is my theory that Alexander Hamilton’s story, though actually one of an immigrant, bastard, son of a whore, is considered more universal than that of Celie’s. I would argue both tell important “American” stories through a specific social locations and constructs that are equally important, but a diverse cast that also includes white people rapping, stepping, and pirouetting is an easier sell even to my teen sons.

But again, I was drawn to the women. I wanted to know more about Eliza and Angelica – their sisterhood, their strength and resilience. I wanted to know how a woman forgives her husband not only for encouraging stupidity (the duels) but also for adultery. It also made me think of how ridiculous our collective sense of morals actually is as we saw the show after Nov. 8 and after the US watched Hillary Clinton be held accountable for her husband’s infidelity while Donald Trump’s three marriages and comment about sexual assault went broadly ignored.

I also loved Lin-Manuel Miranda’s subversiveness – casting of diverse actors to embody historically “white” people, using hip hop and rap to teach U.S. history, and choreography that includes classical, modern and hip hop dance to move not only people but inanimate objects (note “The Bullet” if you go see this show). Art is not just something to consume for comfort, and if you really consider this show it should bother you because it is beautiful and profane. It puts a mirror up to our telling of history and essentially tells us we are fooling ourselves.

Act 3: Allegiance, Asian American women, and Asian American art

There was an Asian American actor in Hamilton, but it wasn’t until the final musical theater experience of the year where my family saw a full stage/screen of faces that looked similar to mine. We took the boys to see a filmed production of the stage musical “Allegiance” at a local theater. Again, this is part of our commitment to our children to give them experiences and exposure to the arts, especially when the story is told by and through the lens of other Asian Americans.

The Japanese Internment isn’t a lesson I recall spending much time on in U.S. history, and my children remember learning about it but briefly. It’s taught in a similar manner as the genocide of Native Americans and slavery. It was a very bad thing that happened but it’s over so let’s get over it. Surely the U.S. government and its true citizens would never let something like genocide, slavery or the incarceration of its own citizens because they looked like the enemy ever happen again…unless it was absolutely necessary.

But until there is some sort of guarantee there will not be a Muslim registry ever, ever, ever there are a lot of lessons in Executive Order 9066. If you think about it, the internment/incarceration was a little bit like taking the things we should’ve learned from genocide and slavery but didn’t and then creating this new thing that waves its hand at the past from the train platform. If you look like the enemy it’s perfectly legitimate to demand you give up everything, including your humanity, for the greater good. You lose your home, your businesses, your humanity in order to prove your worth. And while you are at it, you will work for nothing with no promise of freedom.

And we will call it “camp” so it doesn’t sound so bad. I hear a lot of people really love going to camp.

This is why we took our children despite their lack of enthusiasm. We do not assume they will learn these things at school, connect these dots and apply them to our current situation. My husband and children are American-born citizens. Birthright citizenship for non-whites didn’t matter in the 1940s. That’s why seeing this mattered now.

My dear white readers, you cannot know the power of seeing the big screen full of people who look like you and your family when that is all you know. Hollywood and television. Children’s story books. Cartoons and super heroes. All white, though slooooowly changing, even when it’s a universal story about “America”. Television now has “Fresh Off the Boat” but there really hasn’t been anything on the big screen since “The Joy Luck Club” where our stories were also universal stories.

“Allegiance” is written, produced, and acted by Asian Americans and for me it was powerful because again it was the women – the story of Japanese and Japanese American women, whose stories have disappeared into the background, who kept the families together as well as organized and resisted despite being incarcerated with no due process. It was Kei, played by Lea Salonga, whose ghost connects the past life before and during the Japanese incarceration to the present where her brother Sammy, played by Telly Leung and George Takei, pushes away the memories. Kei lives in the generational and cultural gap by honoring her family while still learning to be the nail that sticks out in order to honor & protect her people and ultimately it is her choices that sets in motion an opportunity to remember and forgive.

And as we are days away from Christmas where my fellow Christians and I celebrate the birth of Jesus, I am once again reminded that women and our stories cannot be relegated the background. We are part of the narrative.