Dear Readers,

Have you heard about the crazy that went down on the Napa Valley Wine Train over the weekend?

So the wine train is a real thing, and my husband and I were on it about 21 years ago for our anniversary, about a decade too early for my tastebuds to fully appreciate what I could’ve been drinking. It’s literally a train that goes through Napa Valley, and you can eat and drink your way through it. It is a bar on wheels. How loud do you have to be to be too loud on a bar on wheels, especially if you are with a group of your reading besties enjoying a good book discussion?

Well, apparently it’s not about being loud. It’s about WHO is being loud and WHO thinks you are too loud. This is not surprising to some of us, but that doesn’t make it any less humiliating, wrong, and racist.

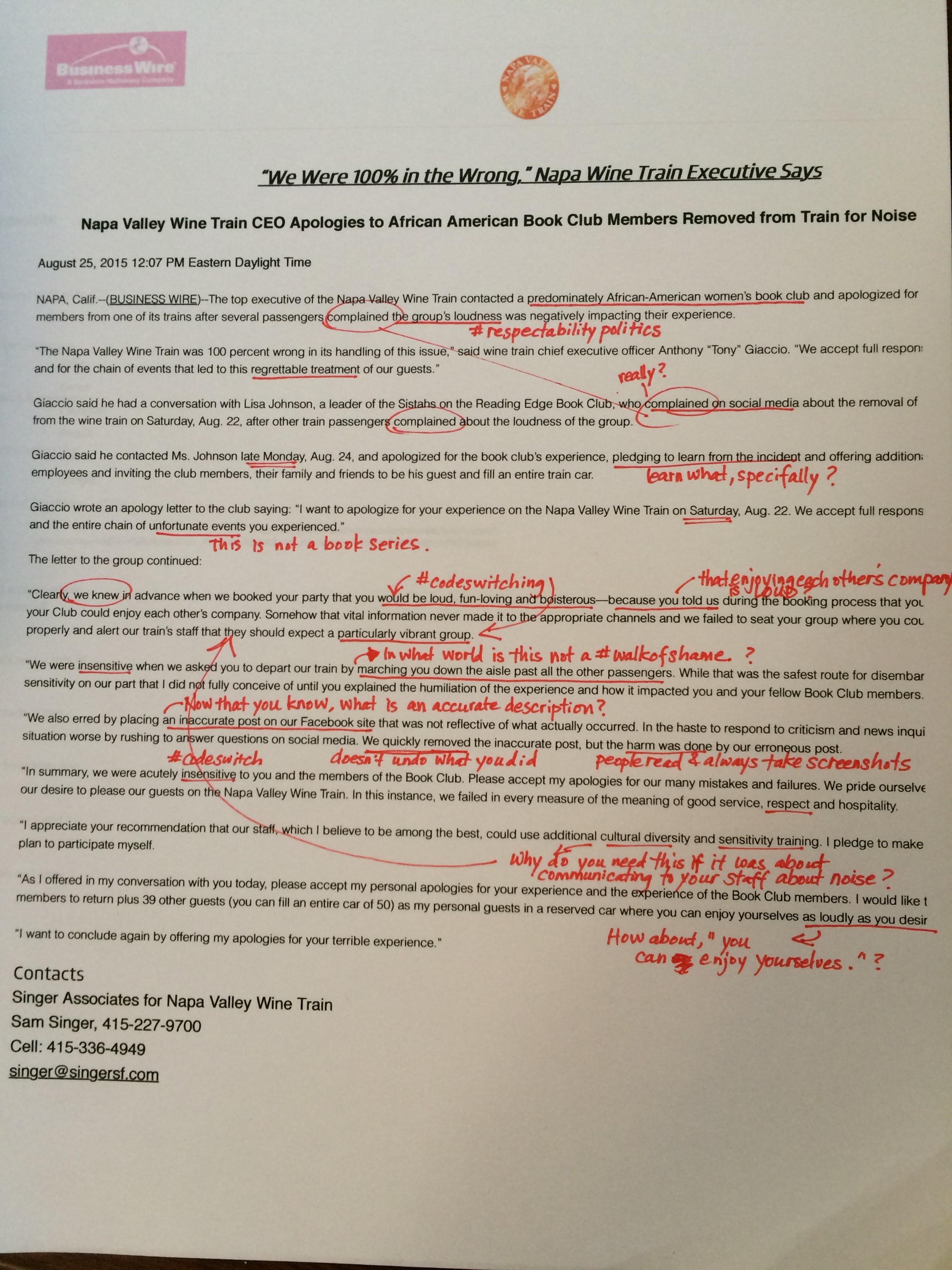

The CEO has issued an apology, and here is where I brought in my love for manuscript Bible study and intersected it with … my life as a Korean American woman of color who pays attention to what happens to other women of color. I looked at the apology and started marking it up with comments, questions, observations. I’m sorry for the quality of the photo, and you may see that the text didn’t fully print on the right margin – user error. But you can get the gist of it. Public relations folks might call it spin. I call it #codeswitching – where otherwise neutral words are used to describe a situation where more precise language connected to race, gender, sexuality, etc. could be used.

For example, when a group of women of color are referred to as “those people” as a way of minimizing the negative racial/ethnic implications of the comment without actually pointing out the obvious.

So that apology to the Sistahs on the Reading Edge Book Club? There is a lot of code-switching going on.

- “…you would be loud, fun-loving and boisterous…”

- “…a particularly vibrant group…”

- “…we were acutely insensitive…”

I haven’t figured out my emotions in response to this situation and to the apology. What I know is that growing up as one of the few Asian Americans in my community I had a different standard of behavior I needed to live up to – for my parents and my Korean American community and for the white community. I had to behave and respect the norm in whichever situation I was in, aka respectability politics. Many times I still believe this is true.

Such was the case for the Sistahs of the Reading Edge.

As you read the apology, what do you read? What are the underlying, unspoken messages that stand out to you? What are the questions you have about my manuscript?